NOAA and the UW team up with Alaskans to create a new tool to predict ice breakup

By Monica Allen, NOAA

Ice forecasts would boost public safety, subsistence fishing, hunting, transportation and commerce

NOAA and the University of Washington have joined with the Native Village of Kotzebue, Alaska, to create a new forecast model that will help predict the spring ice breakup on a major lake outside the village.

Hotham Inlet, known locally as Kobuk Lake, is a 38-mile-long, 19-mile-wide lake that transforms each fall when the ice freezes into a prime place for fishing and a critical travel corridor for people on snowmachines and with dog teams.

The lake is a few miles from Kotzebue, the largest community and the economic and transportation hub in Alaska’s Northwest Arctic Borough. The iced-over lake allows local communities to create an ice road to transport air freight that arrives in Kotzebue to communities around the lake, visit friends and make it easier for people from smaller villages to get to Kotzebue for shopping.

While NOAA National Weather Service ice forecasts provide information about ocean and coastal sea ice and ice breakups on major rivers, there are no specialized forecast models for Alaskan lakes, even large ones like Kobuk Lake, which is fed by two rivers and influenced by tidal flow from the Chukchi Sea.

“This new model we are developing is the future of ice prediction,” said Jiaxu Zhang, the project leader who is a research scientist at the UW’s Cooperative Institute for Climate, Ocean and Ecosystem Studies and NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle. “We want to make it useful and relevant to the people who depend on knowing the condition of ice for safe fishing, hunting, transportation and trade. And the best way to do that is to work directly with the people of Kotzebue on it.”

Unlike traditional ice models that treat ice as one continuous sheet, this new model will simulate how individual ice floes crack, move and pile up — complex processes that are key to predicting exactly when and where Kobuk Lake ice will break up.

For thousands of years, the community has used its Indigenous knowledge and deep understanding of ice to plan their fishing and hunting. But with changing temperatures and weather, this new model which combines physical science with Indigenous knowledge could improve the forecasting of spring breakup for Kotzebue and become a model for other Alaskan and Arctic locations.

The residents of Kotzebue bring valuable knowledge of the ice, the wildlife that inhabit it and the ways they have detected when the breakup is occurring in the past.

Ice fishing provides major source of protein for locals

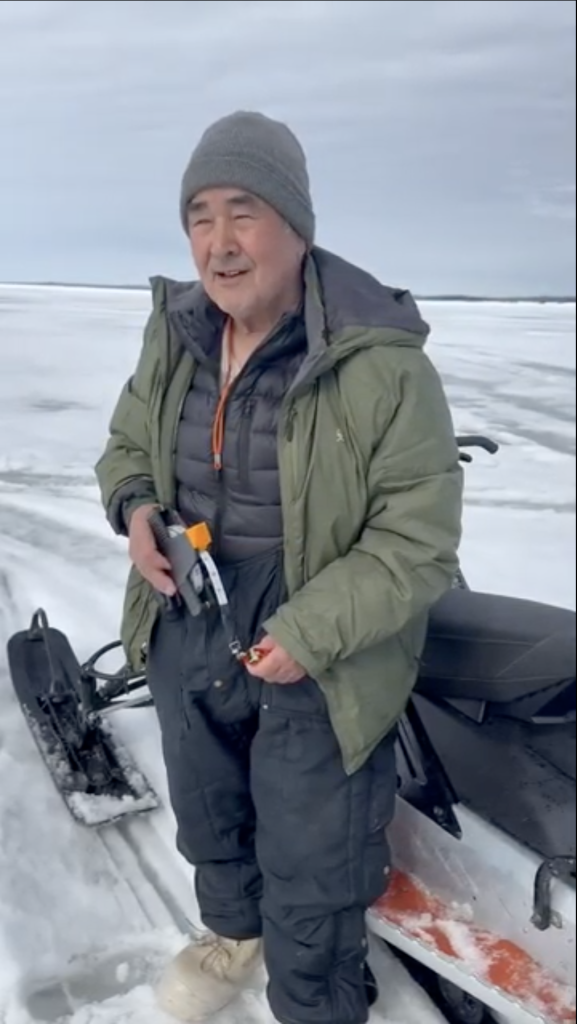

“Fishing here is really important for us,” said Bobby Schaeffer, an elder from Kotzebue who contributes to the project. For Schaeffer and many of his neighbors, much of their protein comes from subsistence fishing and hunting.

Kobuk Lake is well known for a large whitefish called sheefish that can grow as large as 50 pounds. Community members also fish for herring and a variety of smaller whitefish species. These fish are then frozen, pickled or dried to be consumed throughout the year.

The ice fishing season typically begins in late fall and continues into May. In recent years, the ice in parts of the lake has broken up earlier than it did 20 or more years ago, said Schaeffer. He attributes it to the warming atmosphere, which is affecting not only the ice formation and thickness, but all the fish migration patterns, birds, seals and caribou that depend on the lake’s ecosystem.

Team gathers aerial and on-ice observations for model

To create the model, Zhang and her interdisciplinary team collected observations of the ice before and during breakup, including aerial surveys from a NOAA Twin Otter airplane operated by NOAA Commissioned Corps officers and crew. In May, the aircraft was loaded with sensors to take high-resolution images and LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging), a remote-sensing method that uses laser light to measure distances and create highly detailed 3D representations of ice thickness, surface roughness, and environmental features.

In addition to the aerial observations, Schaeffer and Alex Whiting, the Native Village of Kotzebue environmental program director, collected observations on the ground and on the ice. Schaeffer measured the thickness of the ice over time by drilling holes in strategic locations on the ice. Tyler Kramer, a Kotzebue high school student, monitored the salinity of the water flowing into the lake from the Chukchi Sea. By understanding how much salt water flows into the lake and how much of the colder fresh water from rivers blocks that salt water flow into the lake, the scientists have key information for the model about how the warmer saltier water accelerates ice melting from below.

The Kotzebue community members have also contributed a wealth of information about how the breakup has occurred in past years, areas where it is likely to soften first and areas where ice may support fishing and hunting longer into the spring before it breaks up.

Two interesting focal points of the research are the formation of annual pressure ridges running across the lake and recurring thin ice areas that melt out early in the breakup process. While the location of these open water areas reappear in the same place each year, the position of the associated cracks can change from year to year, according to an analysis of satellite images and the current observations. Understanding the forces that cause these phenomena will help to create a successful and accurate breakup model.

The next step to building a model is to create what’s called a hindcast, a validation technique that involves running historical observations through the model and comparing the accuracy of the output to the actual timing of past ice breakups. From this, the team will create and test a model to predict future ice breakup.