Improving Prediction of Arctic Outbreaks Across the Northern Hemisphere

By Theo Stein, NOAA

New research on the Arctic confirms that even as the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the world, cold-air outbreaks from the polar region will continue across the Northern Hemisphere in the coming decades.

The big challenge now is to better understand what triggers these cold-air outbreak events and how to improve their predictability.

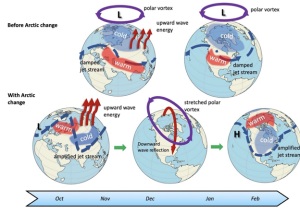

Much of the previous research has shown how a weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex can allow pockets of frigid air to plunge much farther south than normal. The new study, conducted by an international team including Arctic researchers from NOAA, provides additional insights as to how other influences — stalled weather systems, stretching of the stratospheric polar vortex and even events in the distant midlatitudes — can influence these polar patterns.

“A better understanding of these Arctic-midlatitude linkages would improve forecasts covering periods of weeks to months, which would give communities more time to plan for adverse winter weather conditions,” said co-author Muyin Wang, a scientist from the Cooperative Institute for Climate, Ocean, and Ecosystem Studies who works at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL). “The impacts can be more significant as societies conditioned to global warming become increasingly less used to them.”

The study was published in Environmental Research: Climate.

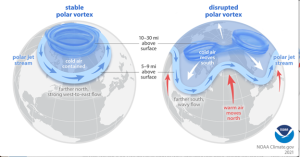

The stratospheric polar vortex is a mass of cold whirling air bounded by the jet stream that forms 10 to 30 miles above the Arctic surface in response to the large north-south temperature difference that develops during winter. Generally, the stronger the winds, the more the air inside is isolated from lower latitudes, and the colder it gets. But sometimes it can be shifted or stretched off the pole toward the United States, Europe or Asia.

“It seems really counterintuitive, but there will be plenty of ice, snow, and frigid air in the Arctic winter for decades to come, and that cold can be displaced southward into heavily populated regions by Arctic heat waves,” said co-author Jennifer Francis with the Woodwell Climate Research Center.

The study, which resulted from an international workshop held in 2023 in Great Britain, provides a new analysis of recent research that offers a pathway to improved forecasts.

The authors said the stratospheric polar vortex has been relatively under-studied in previous reviews of Arctic-midlatitude climate linkages that focus predominantly on the role of changes in the tropospheric polar jet stream. They suggest that future research should focus on the complicated interactions between Arctic, midlatitude and tropical influences.

While many analyses focus on warm Arctic and cold midlatitude events, connections have also been found between unusually cold Arctic temperatures and warm winter events in midlatitudes, especially in Europe.

“Such a range of results confounds those who would like the science to offer a simple way to anticipate seasonal outlooks,” said James Overland, a research oceanographer at PMEL.

One of the complicating factors occurs when a weather system stalls, creating an atmospheric block: a quasi-stationary modification of the jet-stream flow that occurs at middle and high latitudes and typically last for one to a few weeks. Blocking events are associated with persistent weather conditions in the vicinity of the block and frequently lead to extreme weather events in midlatitudes, including winter cold air outbreaks.

Tropical climatic drivers, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and the Madden-Julian Oscillation, can create the conditions that lead to the establishment of these atmospheric blocks thousands of miles away.

The study authors underscored the need for research to better understand how to predict cold outbreaks in lower latitudes, which will help communities adapt to the consequences of extreme cold weather.

“The Arctic may seem irrelevant and far away to most folks, but our findings show that the profound changes there affect billions of people around the Northern Hemisphere,” said lead author Edward Hanna with the University of Lincoln.

The international research team was composed of scientists from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Finland, South Korea, China and Japan.

“The most interesting part of the research is that the polar vortex stretching events could be an important driver of North American cold air outbreaks,” said Amy Butler, a climate researcher with the Chemical Sciences Laboratory who was not involved in the study. “It’s a novel way of looking at how the stratosphere might influence the surface climate. It’s certainly worth understanding better to improve predictability.”

(Material from University of Lincoln and Woodwell Institute press releases were included in this story. See related reporting at the Associated Press.)